-

Credits

- Story by:

- Aleksandra Sagan & Laura Kane

- Edited by:

- Sunny Freeman & Kevin Ward

- Layout & Graphics by:

- Lucas Timmons

- Graphics by:

- Sean Vokey

- Produced by:

- Megan Leach

AMRITSAR INDIA — Chickens squawk from inside wire cages stacked high outside a bustling market street lined with live meat shops. The midday heat's intensity prompts one shop owner to move some of his hens to a shaded loft, where they have a bird's eye view of the butchering room.

By closing time, a worker will stretch their necks over a large tree stump and decapitate them, another layer of blood splattering on the walls, pooling on the floor.

Live chicken markets exist all over India — where the majority Hindu population avoids beef, Muslims swear off pork and the poultry industry is rapidly growing.

As Indians increasingly gravitate to chicken in their meals, Gaurav Rai and his brother are expanding their family's chicken processing business to include the whole supply chain, from hatching eggs to selling birds in their retail shops.

"Antibiotics, we have to use in India," he says, sitting in the Amritsar office of the feed production plant that mixes 800 tonnes of food monthly for the company's 250,000 chickens to consume.

Rai adds antibiotics to his feed about four or five months of the year, when the weather presents challenging conditions. Without antibiotics, chickens could take longer to grow or die of infections.

"If we don't use antibiotic, then in challenging times we might suffer huge losses."

In India and Canada, farmers give their animals antibiotics to fatten them up, prevent disease or treat sickness. Many farmers say antibiotics are critical to ensure the health and safety of their livelihood, but the practice also carries a dangerous cost for humans.

Farmed animals use a staggering amount of antibiotics; in some countries, they consume more than people.

Such unfettered use helps to create and spread superbugs, bacteria resistant to antibiotics responsible for killing an estimated 1.5 million people each year.

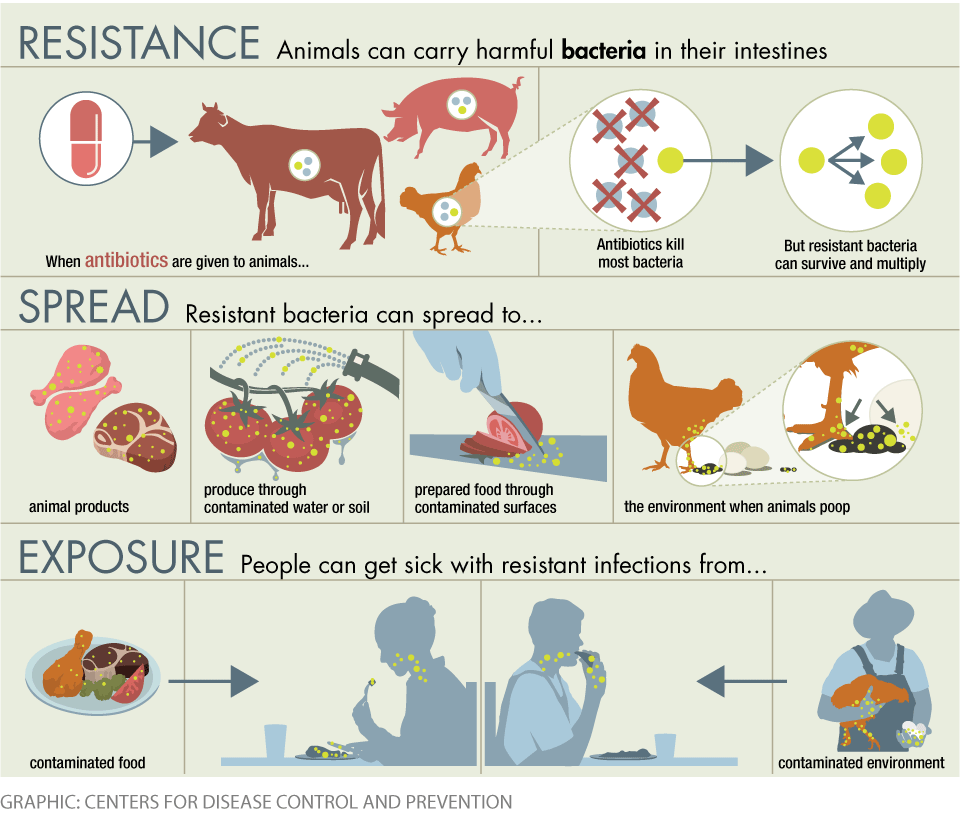

The antibiotics animals consume can eradicate some bacteria, but allow strains that are drug-resistant to thrive and transfer to humans through meat or the environment, making people sick with sometimes fatal drug-resistant infections.

The link between animal medicine and human health prompted NGOs, governments, and even the World Health Organization to push for a reduction in the use of antibiotics on farms.

“If we don’t use antibiotic, then in challenging times we might suffer huge losses.”

Co-operator of a chicken processing company Gaurav Rai

Some nations moved quickly to make changes. But others, including Canada, lag.

Canada will only ban some uses of antibiotics deemed medically important later this year — more than 15 years after identifying using these drugs to promote growth as a possible problem.

In India, meanwhile, few regulations for antibiotic use on poultry farms exist and experts predict the practice will only climb as chicken consumption continues to rise.

If governments fail to curb the practice, they’ll simply enable superbugs to keep spreading and growing.

There is no question that Canada needs to reduce its use of antibiotics, says Ellen Goddard, a professor at the University of Alberta’s faculty of agricultural, life and environmental sciences.

"The public health implications are just so serious. And, the problem is that we're not yet at a stage where we have a substitute for antibiotics. And people are just going to get very sick as the number of antibiotic resistant bacteria grows."

In Amritsar, farmers responsible for flocks of thousands of chickens haul 50-kilogram sack deliveries to the coop twice a day, often unaware if any antibiotics lurk inside. They empty them into feeding stations and keep a watchful eye to ensure their charges are consuming enough to grow to market size.

"One day comes 20 sacks, then another time comes 25 sacks," says Lal Bahdur through a translator, standing in an open-air chicken coop where he's worked for several months watching over thousands of birds. More sacks arrive as the chickens age, getting closer to market weight.

Antibiotics in feed are generally used to prevent various illnesses or to help birds grow faster. Chickens can also receive antibiotics through their food or water if they're sick. When a bird falls ill — which occurs in several hundred out of a typical flock — farmers say they call a doctor who dispenses medicine usually to the entire population.

Farmers rely on medicine also used in humans, including colistin — a so-called last-resort antibiotic used by doctors when no other drugs are working. As doctors in India increasingly turn to colistin, they have started to see resistance to it in some newborns.

Venky's, one of India's largest chicken processors, sells animal health-care products, including antibiotics, to other producers through its website. One of its products, Colis V is promoted as "equivalent to colistin," and sold as more effective in combination with other antibiotics.

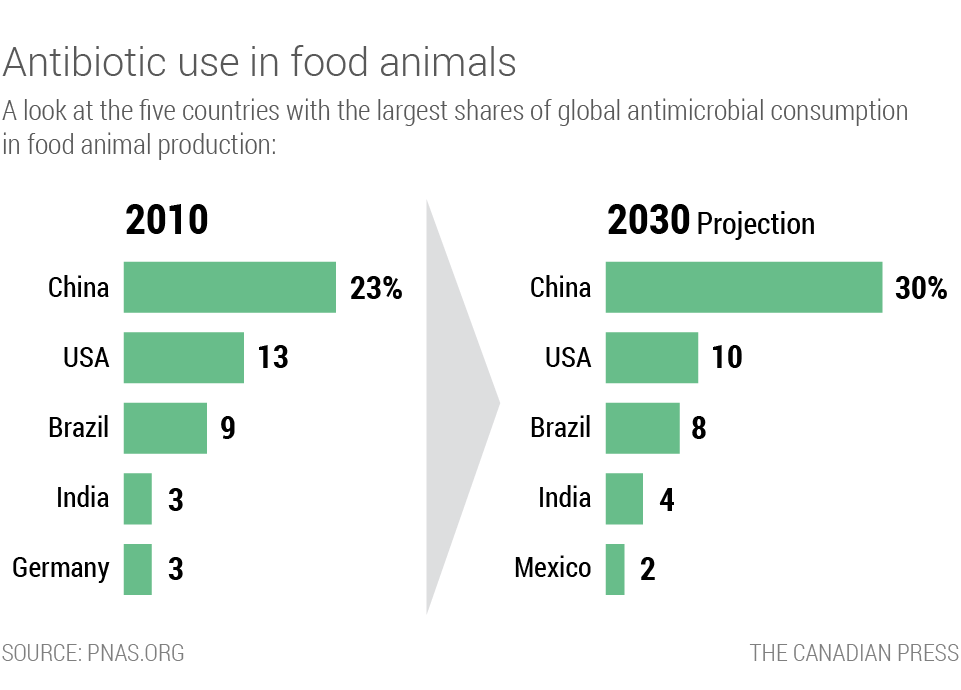

India, tied with Germany, is the fourth-largest consumer of antibiotics in animals, with three per cent of global market share. It is outranked only by Brazil, the United States, and China, according to estimates in a widely cited 2015 study of global trends by lead researcher Thomas Van Boeckel, a spatial epidemiologist studying infectious diseases.

In Canada, gaps in surveillance of antibiotic use on farms obscure the practice's prevalence. The current system, for example, does not monitor use in beef cattle, though consultations are set to begin on how to collect such information.

On Canadian ranches, where cows openly graze on acres of land, ranchers dole out antibiotics mostly as medicine, either to prevent or treat infections.

Sometimes, ranchers prefer to add antibiotics to feed to avoid causing their cattle the daily stress of administering medicine.

"It works very well instead of having to try and rope or catch or corner calves," says Tim Oleksyn, who operates a ranch north of Saskatoon.

But most Canadian producers and industry groups seem to understand the need to scale back both because of the potential fallout to human health and growing demand for antibiotic-free meat.

The Chicken Farmers of Canada, which represents nearly 3,000 farmers, started phasing out medically important antibiotics for the purpose of preventing illness.

Charles Brower, a former resistance researcher now studying at Harvard to become a doctor, tested hundreds of chickens on 18 farms in the Punjab region and found high levels of resistance to antibiotics important for human health.

Four-in-ten samples showed resistance to ciprofloxacin, used to treat respiratory tract and skin infections, according to Brower's findings published in Environmental Health Perspectives in 2017. Nearly 90 per cent showed resistance to nalidixic acid, often used to treat urinary tract infections.

Farmers can pick up the bacteria by interacting with the animals, which they do multiple times a day. The bacteria can also be passed to people who touch or eat contaminated meat or other food products, which can then be spread to others.

Environmental transmission is also an issue. When animals that consume the antibiotics defecate, the manure can spread the bacteria through the ground or leech into water supplies. Some farmers in India use or sell the manure to fertilize crops.

Bahdur cleans his chicken coop every four or so days and then sells the manure for farmers to use on vegetable and wheat crops. A trolly costs about $30.

"Down the line, antibiotics will be banned," Rai says, anticipating a crackdown by the Indian government amid a growing body of evidence that links drug-resistant bacteria carried by animals and transmission to people, as well as a more educated consumer base aware of the danger of superbugs.

He started to move towards antibiotic-free production nearly two years ago. He runs self-directed studies that test the difference between flocks treated with antibiotics and those that receive alternatives, like probiotics. He estimates he cut his antibiotic use by 40 per cent.

Rai's not the only producer scaling back on antibiotics in anticipation of government changes.

“Down the line, antibiotics will be banned,”

Co-operator of a chicken processing company Gaurav Rai

Venky's also says it stopped administering antibiotics for growth promotion about two years ago. Another large producer, Life Line Feeds, says it stopped adding antibiotics to its feed for growth promotion in 2015-16.

In Canada, the industry largely supported government changes set to be implemented in December that require pharmaceutical companies to remove growth promotion claims from antibiotics important to human health.

The move is part of a set of recent changes, including regulations introduced in November that restrict personal importation of veterinary drugs for food-producing animals or those intended to be eaten. Only drugs that do not pose a risk to public health or food safety may be imported in supply quantities for less than 90 days.

Farmers will also be required to obtain a veterinarian's prescription for all remaining medically important antibiotics that are still available over-the-counter starting Dec. 1.

The new policies and regulations have been a long time coming. In 2002, a task force first identified problems with growth promotants and the loophole that allowed farmers to import antibiotics for use in their animals with little oversight.

Canada has been slower to curb antibiotic use in agriculture than most other members of the G7, aside from the U.S. whose changes it followed, says John Prescott, a University of Guelph professor who sat on the board for the now-defunct Canadian committee on antibiotic resistance. The committee produced a national action plan in 2004. It was never implemented.

The European Union, by contrast, banned adding antibiotics to animal feed to promote growth at the beginning of 2006.

Even as Indian farmers operate under the assumption that government changes are just a few years away, experts anticipate that farm use of medicine will only rise in the coming years amid a surge in demand as Indians' incomes rise and more people can afford to add animal protein to their diets.

Estimates suggest demand for poultry meat will jump by about 850 per cent in the country between 2000 and 2030.

India's use of antibiotics on farms is expected to nearly double by 2030 and grow to four per cent of global share, says Van Boeckel's study. Areas of high antimicrobial consumption in India will grow 312 per cent by that year and while India maintains its fourth spot, Germany will fall from the top five, it projects.

India has shifted toward cost-efficient production systems that need antibiotics to keep animals healthy and stay productive, driving antimicrobial resistance, according to the study.

Despite the projected onslaught, the Indian government has yet to implement any heavy regulations around antibiotic use on poultry farms. Even if the farmers are right and it does crack down, there's no guarantee of curbed overall antibiotic use.

Canada's decision to remove growth promotion claims from medically important antibiotics, for example, excludes those that are not considered a top health-care priority which are still used by some Canadian cattle ranchers.

The move also won't stop farmers from potentially using those same medicines for different reasons, though they will require a veterinarian's prescription.

Operators in both countries seem resistant to too much change, fretting over slim profit margins and their ability to care for their animals.

Rai's pre-emptory moves are not without their burden.

He has tracked a measurable difference in the quality of the chickens that consume antibiotics and those that do not; antibiotic-free chickens take two to three more days to grow to a selling size, and mortality among those flocks is higher.

Rai pulls a stack of record books from his operation's 80 farms onto his desk, flipping through them to find examples of antibiotic-free flocks.

He points to one that did not receive medicine and developed a plague of gout. More than nine per cent of the flock died and the birds that lived required 39 days to reach roughly 1.75 kilograms.

He opens another booklet, this time from a farm where the workers fed chickens antibiotics. In 39 days, just 3.3 per cent died and the flock grew to an average of 2.3 kilograms apiece.

Chicken prices in the country are set daily and per kilogram, so that extra 600 grams in the second flock amounts to a significant profit boost.

Canadian ranchers worry they'll pay more for medications after Dec. 1 when a veterinarian's prescription will be required.

"I think you won't find many demographics as frugal as ranchers," says Tara Davidson, a 35-year-old cattle farmer in Saskatchewan.

"We're worried about our bottom line at the end of the day."